(for Travel & Leisure)

(for Travel & Leisure)

Late on a chilly afternoon, a cold rain is falling. It turns dark. The streets empty. The cobblestones are slick. A man seems to follow you. Suddenly, Stockholm—with its sunny summers, star-spangled winter nights, placid harbor, and beautiful blond youth—is recast as a secret, hidden, frightening place. “A day for murder,” says one of the tourists as we descend on Mellqvist Kaffebar.

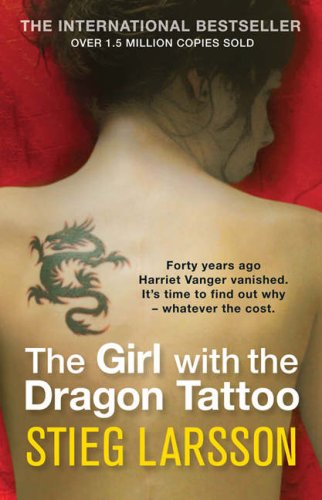

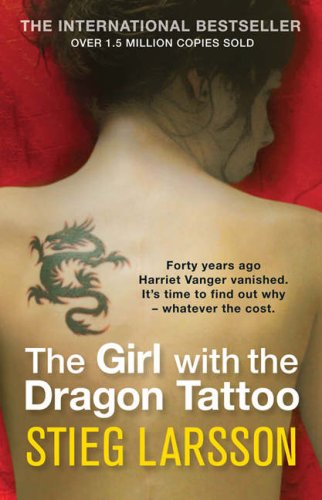

“This is it,” they whisper to one another—the café where Stieg Larsson plotted his Millennium trilogy. Forget Hemingway’s Café Flore, in Paris, or the Grand Café, in Oslo, where a chair is still marked, Reserved, Dr. Ibsen—Europe’s newest literary shrine is this pleasant coffee shop in Södermalm, Stockholm’s bohemian quarter. Led by a guide from the City Museum, the visitors next move on to the local 7-Eleven, where Larsson’s heroine, Lisbeth Salander, shops for Billy’s Pan Pizza. We peer into the freezer at packets of pizza as if at the Shroud of Turin.

It seems that Scandinavia is awash in crime writers, and many have made brilliant use of its geography: Arnaldur Indriðason’s claustrophobic, inbred, bankrupt Reykjavík in Silence of the Grave; Jo Nesbø’s frozen Oslo and its surrounding countryside in The Snowman; Peter Høeg’s ice-locked Copenhagen in the brilliant Smilla’s Sense of Snow. But because of the Larsson phenomenon—more than 60 million books sold to date—I’ve come to Sweden, ground zero for crime fiction.

Quick: What are the things you know about Sweden? ABBA? IKEA? Björn Borg and the Bergmans, Ingrid and Ingmar? Now crime fiction has nearly usurped flat-pack furniture as an important export. The Swedish government has issued stamps featuring Larsson and Henning Mankell, a fellow author of best-selling murder mysteries. Foreign editors have been swarming the country in search of the next big thing. Not to mention crime writers like me—I’m pretty keen to figure out why these books sell like Swedish hotcakes. Maybe I’ll change my name to Nadelsson, but for now, I’ve come to the scene of the crimes—to Sweden’s capital, Stockholm, and down to the rural south. To a visitor, Stockholm is often ravishing, especially in the glistening sunlight, summer or winter. At the juncture of the Baltic Sea and Lake Mälaren, it is two-thirds water and parklands and, with about 1.8 million people, an easy size. At its heart, the harbor is filled with boats that will take you sightseeing through the archipelago, with its small islands and wild beaches.

The world that Swedish crime writers evoke—murder, corruption, rape—feels, at first, like a kind of fever dream. Is the extreme violence of some of the books a kind of catharsis? A Greek drama in modern dress? Are the blood-soaked mysteries connected to an uneasy sense of an unredeemed past, with unsolved political murders and espionage cases? Of fascism always lurking?

Then, too, there is the way issues of class, race, and sex, often tidily hidden in a famously egalitarian country, can boil over; or the way new money comes into conflict with the old verities of the welfare state. For some, the presence of immigrants, of people of color from alien-seeming cultures, feels an invasion.

According to writer Arne Dahl—Misterioso is his first in a series of police procedurals set in Stockholm—geography is to blame. “You could almost say there were ‘ghettos’ built in the outskirts of the city to house the new immigrants, and not many of them find their way into the center,” he says. “Since Stockholm consists of islands, there are natural limits between inside and out.”

And then there’s the weather. The endless dark winter nights can drive people literally crazy. Many Swedish crime novels are famously set when the world seems covered in ice—and when it cracks, terrible things are revealed.

I love winter mysteries—my latest, Blood Count, is set in a snowbound Harlem. Most of my books take place in New York, which is never just casual background, but a major character. For Larsson, too, geography really is destiny—his books have a geographical moral code.

In Larsson-land, the good people live in Södermalm, one of the 14 islands that make up Stockholm. Söder, as it’s affectionately known,was once working-class; now its old warehouses have been transformed into cafés and boutiques.

Here is the apartment of Mikael Blomkvist, crusading journalist and Larsson’s alter ego; there Kvarnen, where everybody eats and drinks—including Lisbeth Salander, the invincible girl-woman punk detective who can hack any computer and put an ax in any man’s head. Inspector Jan Bublanski, the cop with a conscience, attends Adat Israel, the ancient synagogue on St. Paulsgatan. Scenes from David Fincher’s new version of The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, starring Daniel Craig as Blomkvist, were shot in Söder. The rich and greedy live to the east.

“The ‘real’ upper class lives in Östermalm, or in suburbs like Djursholm,” says Jens Lapidus, Sweden’s most popular young crime writer, over a beer at Café Rival, in Södermalm. “And they will look strangely at me, presuming, because I’m a bit dark, I am the cleaning guy from Iraq.”

At 37, Lapidus, a third-generation Stockholmer, is also a defense attorney whose cases often involve immigrants. He gets the city’s geography in his gut. Easy Money, his first English-language novel, comes out in the United States early next year. It describes a crime that links the immigrant communities on Stockholm’s outskirts with the fat city of rich boys and girls wearing T-shirts that read Dad is Paying. It’s the Bright Lights, Big City club set, fueled by sex, booze, and cocaine.

JW, his main character, is an ordinary guy from the provinces. He gets caught up in crime to fund his obsessions, which include a Rolex watch, a Prada jacket, and a BMW. He might be among the crowd of stunning clones—tall and fair, skinny pants, pointy shoes—that floods the bar at the Nobis Hotel, where I’m staying.

Stockholm is never twee. Its broad-shouldered imperial buildings—parliament, a lavish opera house, the Grand Hôtel, where Nobel Prize winners strut their stuff every December—recall a country that once owned a large part of Europe. It seems a veritable urban idyll.

My hotel, as a friend points out, is next door to the bank where, in 1973, a famous robbery took place: the hostages became attached to their captors and the phrase Stockholm syndrome resulted. At NK, the Art Nouveau department store nearby, Anna Lindh, the minister for foreign affairs, was knifed (and killed) in 2003. Like Prime Minister Olof Palme, murdered in 1986, she was not protected by Swedish security forces. Swedes are still obsessed with Palme’s murder, which has never been solved.

During my last days in Sweden, I go down to the southern province of Skåne. There, in a town called Ystad, Kurt Wallander—the hero of Henning Mankell’s novels, a gloomy cop with a lousy personal life—yearns for a more Swedish past.

I’d imagined that Ystad was a creepy place, with noirish alleys hiding vicious criminals. It is, in fact, a lovely port town with pretty old squares, a little opera house, and, as often as not, wonderful weather. Much of Skåne is farmland. Long, ripe fields run down to the beaches. In the summer, holidaymakers picnic and swim, and the outdoor markets sell fabulous potatoes.

In my favorite Mankell book, One Step Behind, the discovery of the bloodied bodies of beautiful young people turns this sun-kissed scene into a terrible tale. Easy to forget sometimes that this is Strindberg territory—an isolated population in a cold country, part of it above the Arctic Circle—with frozen vistas, frozen emotions, and only blood to break the ice.