A resolute New Yorker falls unapologetically in love with this western town in the middle of nowhere—or rather, nowhere that writer Reggie Nadelson could have ever imagined.

A resolute New Yorker falls unapologetically in love with this western town in the middle of nowhere—or rather, nowhere that writer Reggie Nadelson could have ever imagined.

In an art gallery in Livingston, Montana, I meet a man who has been attacked by an elk. He’s an art dealer, and as he drove through Yellowstone Park, an elk crashed through the window of his sports car and almost killed him. I can’t shake the image, any more than I can lose the one of another man who told me he had been mauled by a bear. The bear reared up in sunlight while the man lay in the dark woods, then fell on him, and while he lay there the man could feel the bear’s heart beat against his own. Even here in this civilized little city in south-central Montana that has good art and more bookstores than gun stores, in a part of the world so luminously beautiful, so tender, really, in its muted colors you feel as if you’ve stumbled into Shangri-la, there is always something raw, something wild, and near the edge. It’s a potent, alluring combination.

For the third time in as many years, I’m back to stay near Livingston at Chico Hot Springs. And I can’t remember now how I got here in the first place, how I heard about Chico. It stuck in my head, though. I had always wanted to come here. Montana was an idea you could roll around in your mouth and it would conjure up the myths: Lewis and Clark opening the West; the legendary gold strikes of the 19th century; the fabulous mining towns that went bust in the 20th; the cowboys and Indians, writers and ranchers and movie stars; the epic scenery and vast spaces in a state that’s bigger than New York and has 800,000 people.

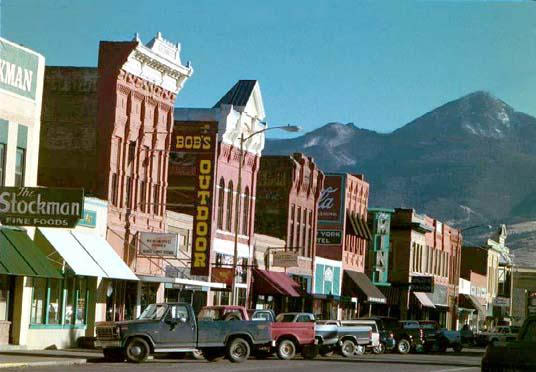

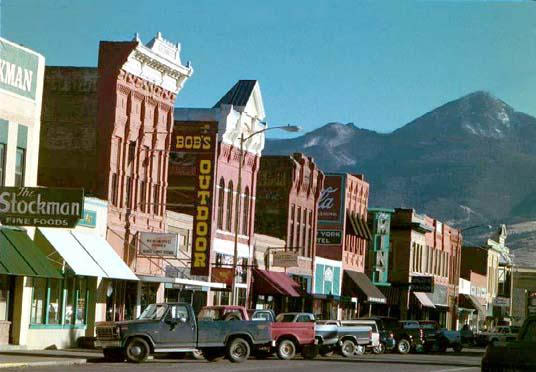

On that first trip, I drove through Livingston, a tidy town of 7,500 with its lavish, Italianate train depot and red-brick buildings from the 1880s. Through Livingston, then down 540, a rolling back road, and on and on, and after a while I figured I was lost. Lost in a landscape where high blue mountains come down to a lush river valley so that the light bounces; where the water that irrigates the farms sprays prisms of color against green fields early in the morning.

Then, just like Oz, it was there: Chico Hot Springs. At the end of the long front road that doubles as a landing strip for locals who fly in for the finest food in Montana—Harrison Ford sometimes comes out this way—I saw the hundred-year-old inn, white paint, green shutters. Out back, a couple of horses hung around. Kids spilled onto the grass after supper.

For me, Chico is paradise, but it’s not for everyone; it’s comfortable but unfancy (though numbers 430 and 603 are elegant, with canopy beds, hand-tiled tubs and lots of light). There are no phones in the rooms. There are no TVs, there’s no room service. This is a place to unwind and forget what time it is, a place to read a book in a green Adirondack chair on the porch. To swim at midnight in a pool fed by hot springs. To drink a great martini in the bar, eat halibut flown in for dinner (Chico has, by consensus, the best restaurant in Montana), grab a beer in the saloon or head up to Livingston for a little shopping. It seemed a long road that first time, but locals sometimes drive the 25 miles up and back more than once a day. Livingston is what passes for urban life. There’s no traffic here. Plenty of stars at night.

“Set your watch back fifty years, maybe seventy-five, and this is Aspen,” says the ebullient Mike Art, who with his wife, Eve, owns Chico Hot Springs, and runs it with plenty of style. They call Mike “The Godfather of Paradise Valley.”

People come out here to hunt or hike or ride or boat, and Chico can arrange it all on an ad-hoc basis. (But if you’re looking for a more organized dude ranch where you book in for at least a week, where haute dinners are at set times, the kids can be programmed from dawn until dusk, and the cabins are rustic à la Ralph Lauren, try the gorgeous Mountain Sky Guest Ranch). But most of all, people come to this part of the world to fish. There is, it’s generally agreed, some of the best fishing on earth. Even I caught a fish.

In Paradise Valley, where the Yellowstone River is undammed and Robert Redford filmed A River Runs Through It, I catch my first fish, a trout. It’s a seductive experience for a completely urban soul like me, this drifting in a boat with a handsome guide in the empty landscape under the enormous blue sky, floating my line on the water, waiting for the hot sun to draw the fish up toward the surface.

“The last best place,” people call Montana, and maybe I’m hooked. Livingston, the river, and Paradise Valley are of a piece. Livingston is still a country town where everyone knows everyone, and Main Street stops at the mountains. At dusk, the astonishing collection of neon signs—the Murray Hotel, the Owl Lounge, the Mint, the movie theater—blinks on.

At Sax & Fryer, John Fryer, good-looking in his narrow, pressed jeans, tots up your books on the gleaming 1920s adding machine that his father used—in the shop that his father opened in 1883, a year after the town was founded. Fryer himself can’t see the point of a computer and he doesn’t take credit cards. Johnny’s grandfather sold fishing tackle and anything else he could get his hands on. I look around at the erudite selection of books, many by local authors. Was Livingston always a bookish town?

“My mother,” Fryer says “called Livingston High Bohemia.” He then goes on to deliver one of those verbal snapshots of the West that people suddenly part with when they’re feeling gregarious.

“I always had this vision of my mother as a young girl; she came from North Dakota from this very isolated part of the world, and I saw her as a farm girl on a ridge, although I could never understand how she knew so much and had such style. Finally, she said to me: You know, every year we got the train and we went to Chicago and New York, and if the harvest was in, we went to Florida for the winter.”

Here, stereotypes fall apart. It’s still too remote for corporations, so there’s no GAP, no Starbucks. The real money is found up around Bozeman, where, at the airport, the Guccis and Vuittons pile up next to the fishing tackle and skis, and the dot-com millionaires fly in from Seattle. Architects are jammed up with work in Bozeman, and property prices are soaring.

One block from Fryer’s shop is Russell Chatham’s gallery. A gangling, birdlike man with white hair, Chatham is a seminal figure in the Livingston creative community. There’s the mix of self-deprecation and self-protection I think I detect in other local artists, as if they all know they’ve stumbled into paradise and don’t want to let the word out. Chatham does want his work seen, though. He makes money from his lithographs, and his paintings are hard to come by because they’re snapped up fast. His are intimate landscapes, many of the valley and the river that flows from Yellowstone Park 50 miles south of Livingston. Chatham has reinvented his Montana in subtle, exquisite, monochromatic colors. His pictures are collected by, among others, the writers and actors—Tom McGuane and Jim Harrison, Peter Fonda, Jack Nicholson—who have settled here or visited Livingston or the ranches around it.

Maybe it’s the rumor of celebrities that gives this part of the world its buzz; maybe I’ve simply succumbed to the possibility of a glimpse of Meg Ryan in the bookshop or Jeff Bridges at Chico, or to those photographs of Robert Redford in the Murray Hotel and in the Sport Bar, with its punched-tin ceilings and pale ale on draft served in jam jars. Maybe their presence is like the faint and unexpected fizz of Champagne on a porch somewhere in the middle of the outback.

One night at Chico, Mike and Eve Art throw a party for friends and neighbors. A hundred people circulate, drinking cocktails; out here, whether it’s wine, scotch or a martini you’re sipping, everyone calls them cocktails. There are grilled artichoke leaves, spicy shrimp, and Peter Fonda in jeans and a denim jacket, looking like 30. Genial and neighborly, Fonda is with his blonde wife, Becky, who was once married to novelist Tom McGuane.

Soon after McGuane got here, he wrote The Missouri Breaks. Hollywood came calling. They were wild times, according to Mike Art, who himself had just arrived, having bought Chico Hot Springs when it was a wreck. It was 12 years before he saw a profit. Steve McQueen once tried to buy the place from him. And Sam Peckinpah had a cabin in the wildest part of the woods.

On the other side of the lawn are Margot Kidder and daughter Maggie (whose father is Tom McGuane), and Maggie’s husband, Walter Kirn, one of the best young writers in America.

McGuane subsequently married Laurie Buffet, sister of Jimmy, who on a visit to town wrote “Livingston Saturday Nights,” about cowboys and bars and poolrooms. There are still a lot of bars in Livingston. Fewer cowboys.

And McGuane’s friends came, Jim Harrison, for instance, who wrote Legends of the Fall, and Russell Chatham, who painted the valley. At the Chico party tonight, there is even a movie agent, a suave man with white hair who talks movie deals. And an Englishman or two. Later in the evening, a Czech architect from Bozeman turns out to be a nifty dancer. Walter Kirn, from Minneapolis, tells me that after a decade in New York he still hadn’t learned to love the city, and that Livingston is a place a writer can live and never long for New York. This isn’t the Hamptons, though. The community protects its own. No one in town stares at the occasional movie star. No one dresses up, either. You can grab lunch at Rumors (good salads, fresh-squeezed juice) or The Stockman Bar (great fries), order a cocktail at the Murray Hotel & Lounge, and never get out of your jeans. Old jeans. Regular jeans. This is the most antifashion place I’ve ever been in my life. In summer, you wear cutoffs or old shorts. Maybe, on a really grand occasion like the party at Chico, a pair of Bermuda shorts gets trotted out, or the sort of cotton summer dress you could have worn 30 years ago.

“Out here, you’re a good guy until you prove you’re a bad guy; that’s all anyone cares about,” says Mike Art. Livingston is a live-and-let-live kind of place, libertarian, free of zoning, notes Jamie Harrison, a novelist who writes mysteries about the town and is also Jim Harrison’s daughter. It is also, she adds, a little rueful, “free of good Parmesan.”

Even the most celebrated actor or writer, even Ted Turner on his 120,000 acres north of town, is dwarfed by the place itself, its beauty, its rigors. Everyone is subjected to the same rough winters, or to the wildfires that rage in summer, devouring the countryside, moving faster than a man can run. Last summer, fires wiped out thousands of acres of Montana. Even around Livingston, a hundred miles from the nearest blaze, the skies were often smudged with smoke. On bad days, ash fell. I was there. At Chico, we watched the sky a lot.

Tough times are nothing out of the ordinary for Livingston. The ebb and flow of its fortunes was dictated for a century by the railroads. Livingston was founded in 1882, the year that the first construction train came through. The red-brick buildings that line Main Street are the kind you see in railroad towns all over the West, though few have been as tactfully restored as Livingston. The depot is now a museum, and the sepia portraits of early workers, miners, settlers, stare out at you with a kind of ascetic determination to make their home in this place, lost among the spectacle of the northern Rockies.

Livingston was also the original stop for Yellowstone, the country’s first national park, which opened in 1872. It’s not hard to imagine the Victorian families, the ladies dressed in petticoats, the men in white summer suits and boaters, putting up for a night in town before heading for the glories of Yellowstone and Old Faithful. Even in the 19th century there was an effort to make the West into a kind of theme park, to tame the spectacle, corral its beauty, promote its exoticism. The real West and the tourist version had already begun to merge; families were picnicking in Yellowstone when, in 1876, George Armstrong Custer made his last stand against the Sioux—also in Montana.

Like the Grand Canyon or the Statue of Liberty, Yellowstone is something you have to do at least once—drive it, hike it, wander its byways, watch for the animals, sit by Old Faithful and wait for it to spout. For me, even better is the drive up over the Beartooth Mountain Highway, described by Charles Kuralt as the most beautiful road in America. You head down to Yellowstone from Livingston, cut through the northern edge of the park, then up over Beartooth. Up 10,000 feet, where even in high summer it’s cold and there are crystalline mountain lakes. Buy a few sandwiches at the ramshackle store. Take them out by a lake, where, in this otherworldly place, you are virtually alone but for the wildflowers and the thin air.

Then I’m back in Livingston. Back in Russell Chatham’s gallery, gazing at the pictures of the places I now know, wanting to buy one, to take one home. In Chatham’s Montana, a man stands at dusk fly-fishing on the banks of the Yellowstone. The snow falls on his prairies. You can smell the rain, the smoke. If I take a picture home, I can remember this Montana, this peculiar, seductive place that I thought about for years before I found it at the end of that long road.

BIG SKY BASICS

Chico Hot Springs Resort 1 Chico Road, Pray, MT 59065; 800-468-9232; www.chicohotsprings.com Mountain Sky Guest Ranch Box 1128, Bozeman, MT 59715; 800-548-3392; www.mtsky.com Chatham’s Livingston Bar and Grille (drinks/dinner only), 130 North Main Street, Livingston, MT 59047; 406-222-7909 Rumors 102 North Second Street, Livingston; MT 59047; 406-222-5154 The Stockman Bar 118 North Main Street, Livingston, MT 59047; 406-222-8455 Murray Hotel & Lounge 201 West Park Street; Livingston, MT 59047; 406-222-1350; www.murrayhotel.com Sax & Fryers 109 West Callender Street; Livingston, MT 59047; 406-222-1421 Russell Chatham’s Gallery 120 North Main Street, Livingston , MT 59047; 406-222-1566; www.russellchatham.com